William Alexander Pinkerton, immigrant ancestor, was born around 1740 in Firth of Tay, Dundee, Scotland. In 1793 he was killed by Native Americans in Pennsylvania while he working in the fields, with his wife looking on in horror. Alexander, his son (1783–1837), was born in Allegheny County, and became a cabinet maker. After living in New Castle, Pennsylvania for a while, he took his pioneering family on a flatboat down the Ohio river and up the Muskingham, and settled in a new town called McConnelsville, Ohio. His son, David (1817–1894) became an Ohio district court judge, postmaster, and first Treasury Department comptroller in Washington DC. David died in Washington DC in 1894.

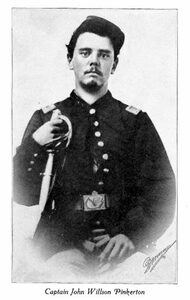

David Pinkerton’s oldest son, John W. Pinkerton (1843–1922) fought in the Civil War. After the war, John W. became a wholesale grocer in Zanesville, Ohio. From there, he developed a new chewing tobacco formula, founding the Pinkerton Tobacco Company in 1887. He incorporated the company in 1901 with 945 shares of stock.

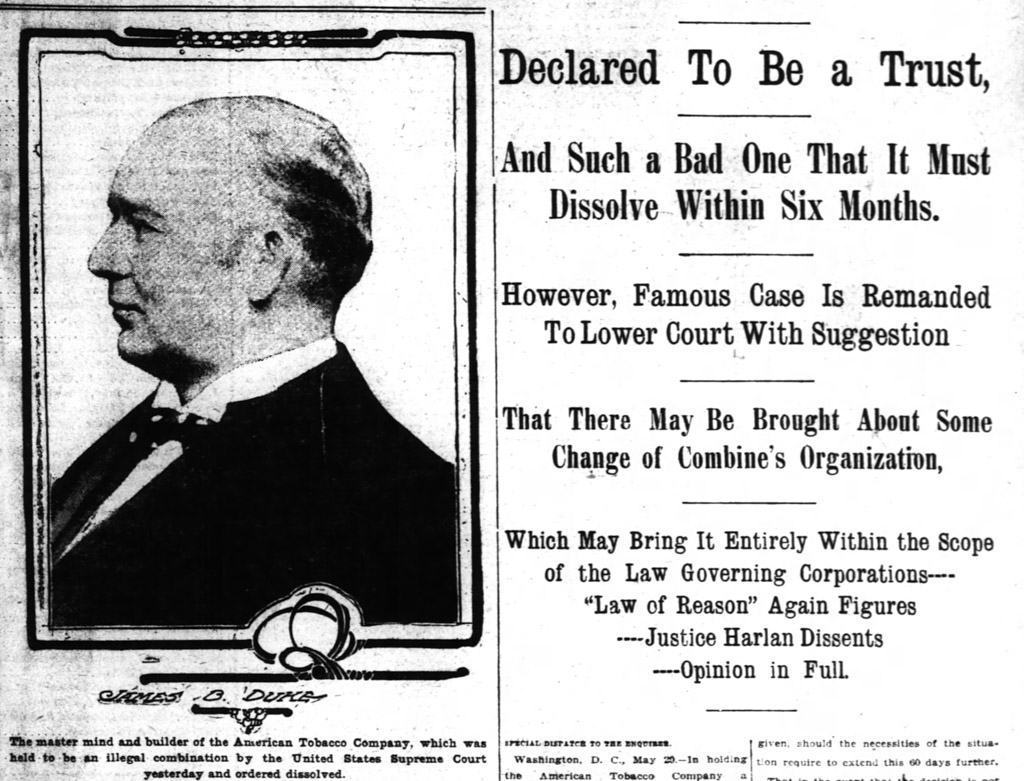

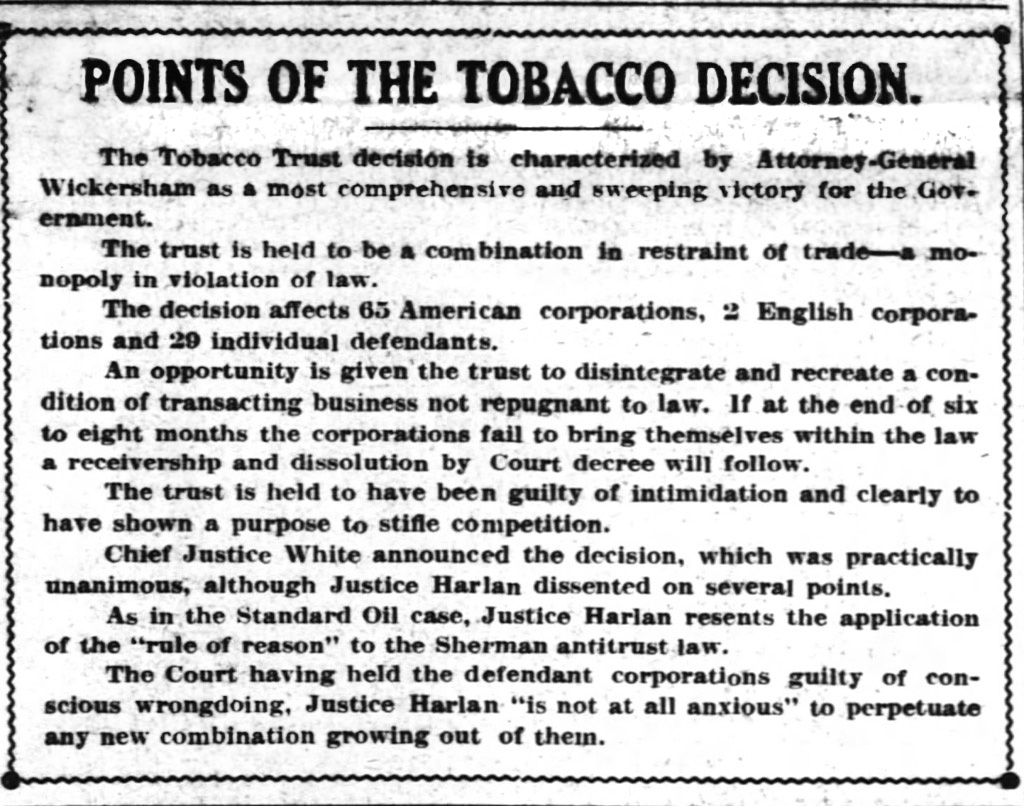

It was an interesting time in history because concurrently, the notorious monopolist, James B. Duke, of North Carolina, was aggressively buying up tobacco companies and putting everyone who was not with him, out of business. Duke and his “Tobacco Trust,” the American Tobacco Company, tried to own the entire tobacco market, unconcerned with breaking the 1890 Sherman Anti-Trust Act, an anti-monopoly law that was enacted the same year David Duke incorporated his business. Duke was big trouble for everyone in the tobacco business, – from the growers to the factories – including the Pinkerton Tobacco Company.

How the Pinkertons came to Toledo

This was never a family story, but I’ve discovered some unsavory monopolistic circumstances that led to the Pinkerton family’s move to Toledo.

It all began down in Zanesville Ohio in 1903 when the Pinkerton Tobacco Company’s treasurer, George Monypeny embezzled a sizable amount of money from the company. This loss of money and employee trust prompted John W. Pinkerton to sell his majority shares of stock to the Continental Tobacco Company in order to get George Monpeny and three other Monypeny stockholders out of his business. Unfortunately, Continental was owned by the American Tobacco Company.

All went well until January 1907, when John W. was summoned to New York to meet with the American Tobacco Company, when they told him that they were forcing control of his company. John W. was jaw-droppingly shocked.

And so, from that date on, the American Tobacco Company dictated what the Pinkerton Tobacco Company was to sell, where they could sell it, what size packages they could sell, and the price they could sell it for. It was all for the purpose of putting companies out of business or forcing them to sell their business to James B. Duke’s American Tobacco Company.

One of the casualties was the J. F. Zahm Tobacco Company in Toledo, which Duke and the Tobacco Trust forced out of the tobacco business in 1907. The president, Mr. Zahm was so troubled that one December afternoon in his office at the factory, he put a bullet through his head.

14 months later, in 1909, at the direction of the Tobacco Trust, this same factory building became the new headquarters of the Pinkerton Tobacco Company. Those were the sad circumstances that brought the Pinkertons to Toledo. No wonder the effects of the tobacco monopoly were skipped over in our family lore.

John W.’s oldest son, Sherwood Pinkerton Sr. (1867–1939) managed the factory to start. They manufactured chewing tobacco and Sunshine cigarettes.

How terrible the casualties of the greedy monopolist. And to be forced into submitting to their whims. Yet back then, at least John W. could see the light at the end of the tunnel. The anti-trust lawsuits had been making their way through the courts, beginning with Teddy Roosevelt’s election in 1904. Finally, in 1911, by order of the Supreme Court, James B. Duke’s monopoly, the American Tobacco Company was divided into three companies, and Pinkerton Tobacco became a subsidiary of Liggett & Myers. John W. Pinkerton resumed control of his company, and the monopoly-busting of 1911 led way for the booming economy of the Roaring Twenties.

A family business

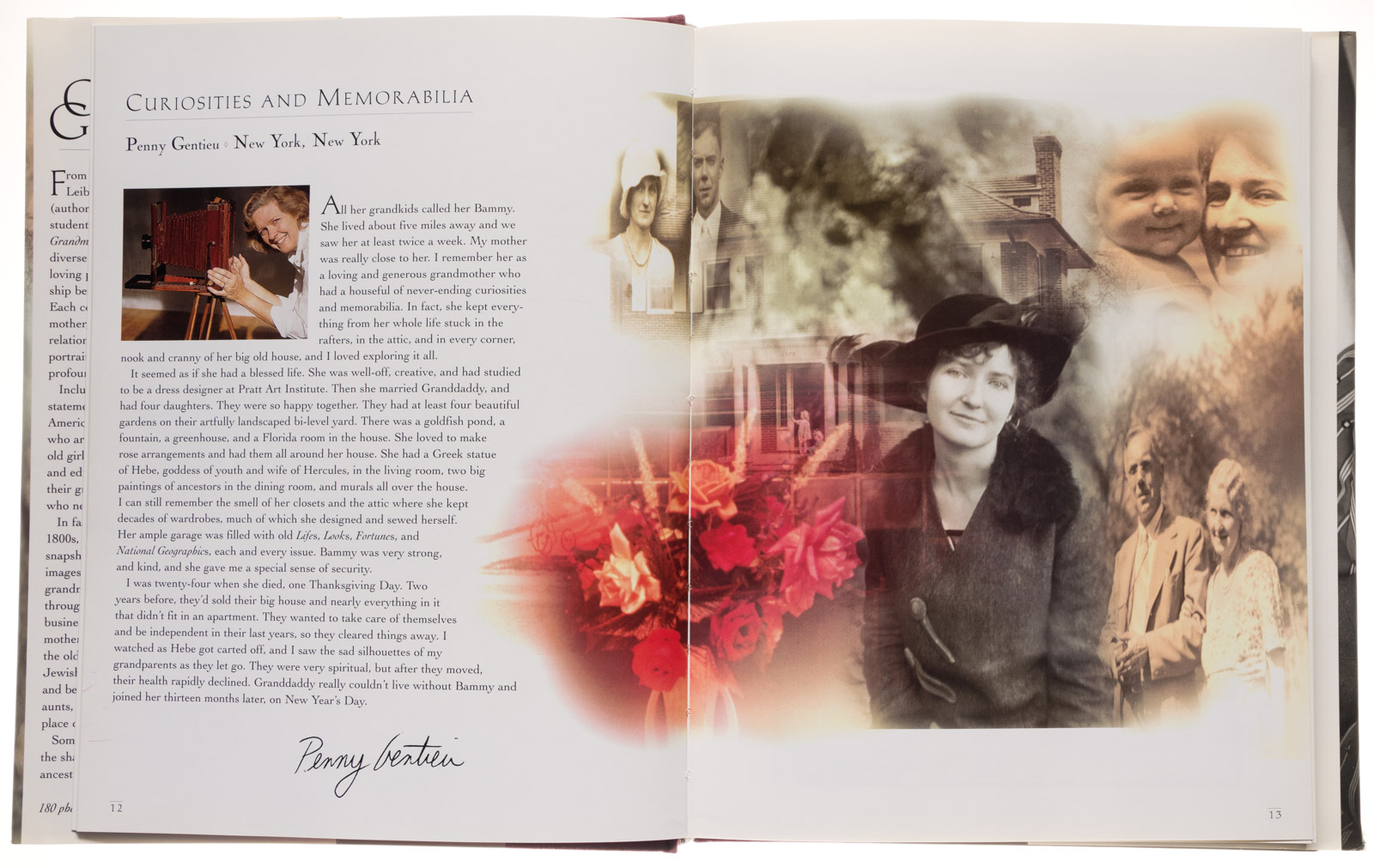

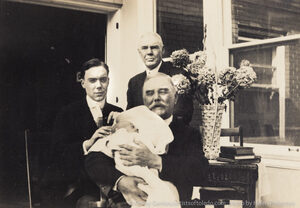

Sherwood’s oldest son, Sherwood Pinkerton Jr. (1893–1980) was my grandfather. He turned 16 in 1909, the year the family moved to Toledo. They lived at 2510 Parkwood. Sherwood, a 1912 graduate of Toledo Central High School, graduated from the University of Michigan in 1916 with a degree in chemical engineering.

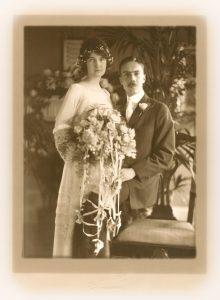

Sherwood served in the Ordnance Department of the U.S. Army during World War I. While stationed in Washington D.C., he met Helen Moyer. (“The first time I saw her in 1918, my inner voice said, she’s the one,” my grandfather would tell us.) They got married on a Tuesday in June 1919, towards the end of the Spanish Flu pandemic. They built a house in 1927 in the new Toledo neighborhood of Westmoreland. They had four creative daughters – one who became the inspiration for my website, artistsoftoledo.com, my mother – Audrey Pinkerton Gentieu (1922–2009).

Sherwood Jr. ran the family business for many years, becoming president in 1940, and retiring in 1959. He developed new chewing tobacco flavors. He put the first woman on the board of directors and instituted an employee retirement plan. After Sherwood retired, the company moved to new facilities in Owensboro, Kentucky. John W.’s greatest legacy to his family, his chewing tobacco company, managed to sustain three generations of the Pinkertons, all because monopolies were busted in 1911.

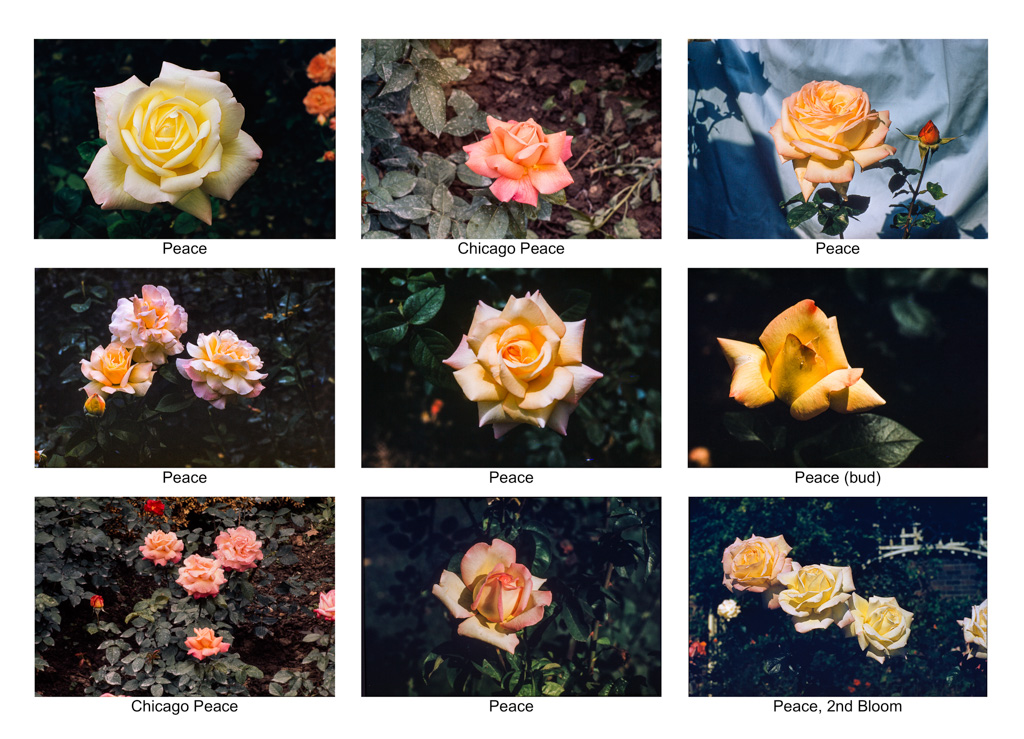

Sherwood Jr. had a blessed life, seemingly free of the business problems his grandfather faced. Besides personally enjoying the chewing tobacco he cooked up and brought to market, Sherwood Jr. and his family embraced the finer side of life, such as photography and roses. John W. bequeathed to my mother and my grandparents a life of grace and happiness. In turn, my Pinkerton grandparents were, to me, a major source of security and affection, and somehow I inherited the photo gene.

John W. would say to his grandson, Sherwood Jr., that retirement isn’t good for some people, if you lack activities you will shrivel up.

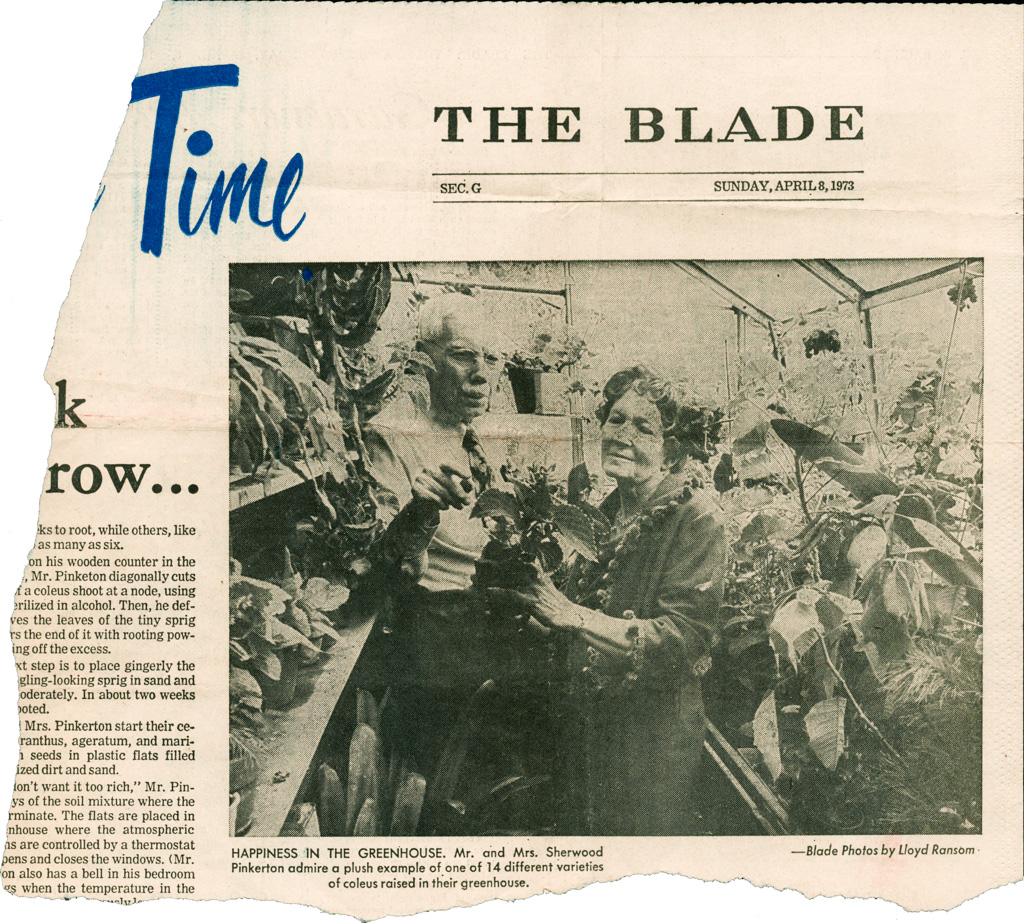

Sherwood proved to be excellent at retirement, as he cultivated roses for 17 years after he retired, and for at least 31 years before. Sherwood was Toledo’s first Rosarian. He gave up his rose garden in 1976, when, in their eighties, he and Helen decided they had to downsize and move into an apartment. Their health declined after that. Helen died on November 22, 1978, and Sherwood, who could barely live without her, died on New Year’s Day, 1980.

The Pinkertons lived in an elegant Georgian Revival house at 1978 Richmond Road. They created four beautiful gardens in their artfully landscaped bi-level yard, including a formal rose garden, an informal rose garden, a shade garden, a goldfish pond, a fountain, and a greenhouse. They had a Florida Room in the house. Their house was filled with never-ending curiosities and memorabilia from their long lives, stuck in the rafters, in the attic, in every corner, nook and cranny. It was a treasure hunt for their 13 grandchildren to explore.

The Pinkertons held an estate sale in 1976 and moved out of the house.

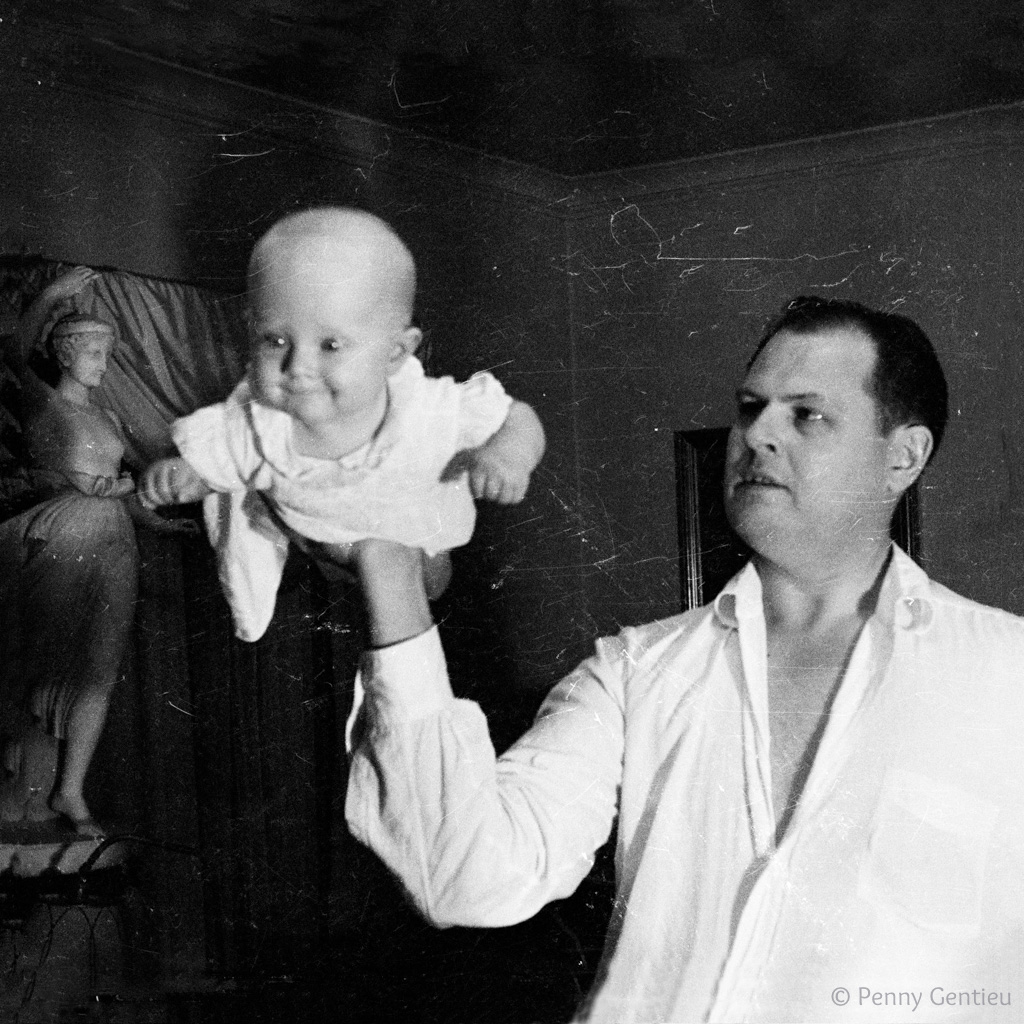

In their living room was a neoclassical marble statue of Hebe, the goddess of beauty and youth, and wife of Hercules. Hebe is the one, in case you are interested, who brought the nectar (the drink of eternal youth and immortality) to the feasts.

The statue came from Italy, a family heirloom passed on to Sherwood by his Great Aunt Julia who picked out the statue with her U.S. Ambassador husband while on an overseas trip. Julia died and bequeathed it to Sherwood in 1911, the same year of the federal trust-busting that would benefit the Pinkerton family for the rest of their lives and on to the new generations. Next to the fireplace in their living room, Hebe appeared nonchalantly and purely incidentally in family photographs over the fifty years they occupied the house.

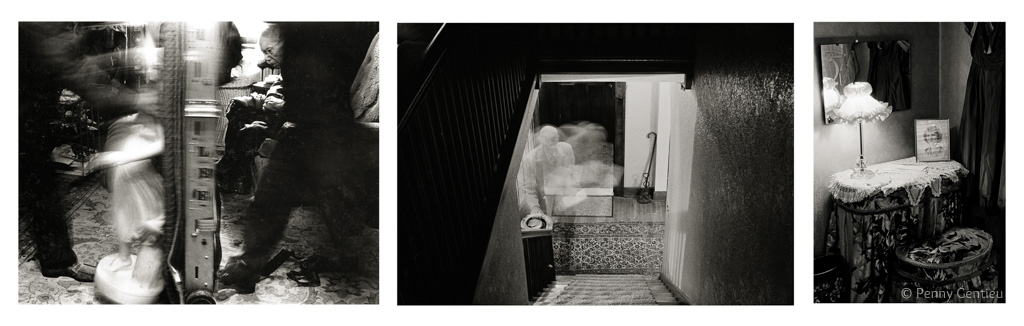

Then one day Hebe was picked up by movers and shipped to their daughter Julia, in Portland, Oregon. I captured that moment, one of my first black and white photographs, because the moment felt like a dichotomy, my grandfather letting her go.