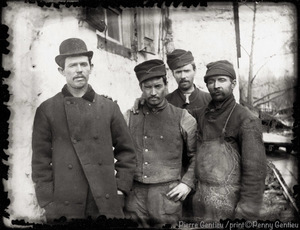

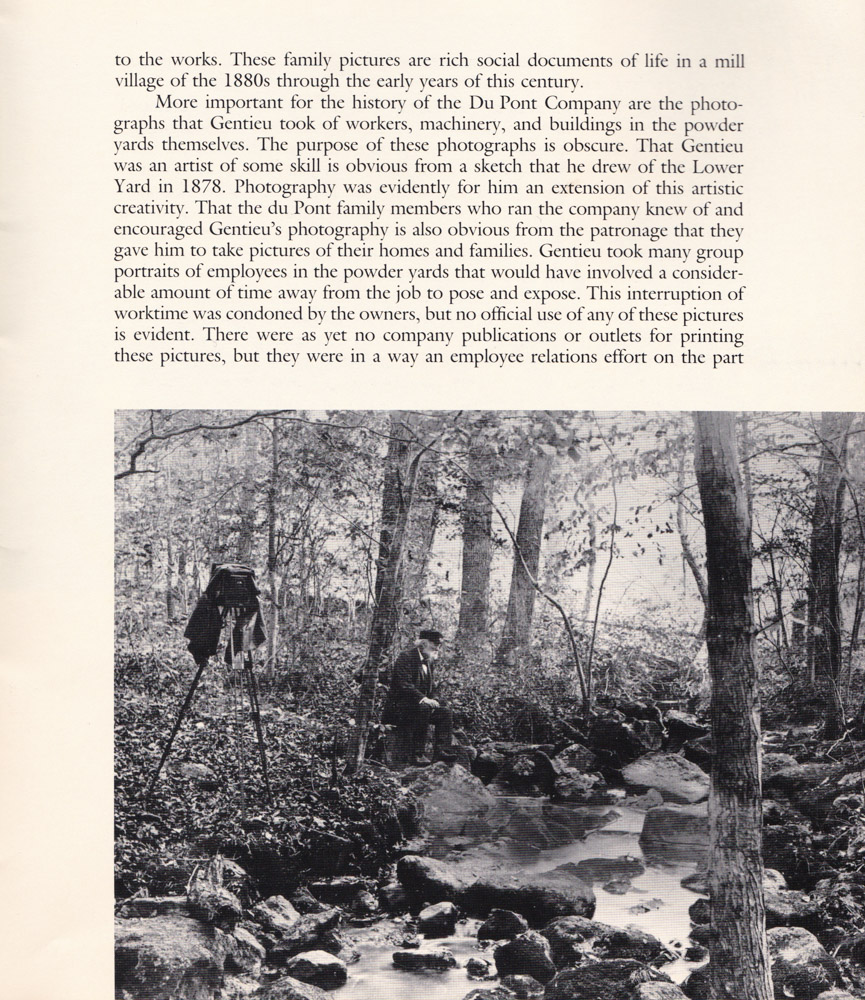

My great great grandfather, Pierre Gentieu, was a photographer. He created sharp-focused, sensitive images of the workers and families who worked at the DuPont Powder Company. His photos express the hard life of the workers, many of whom were new immigrants, at the first big industrial company in the United States, which happened to be situated in the most photogenic location there ever could be for a gunpowder corporation, along the banks of the Brandywine River in the rolling hills of northern Delaware.

During my last year of college, I took a photography class, and suddenly everything seemed to fall into place, and I got instant recognition for my photographs.

I became a professional photographer in New York. In 1988, I had a show called “Confabulations” at a gallery in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, and that show was written up in American Photographer magazine.

A few years after that, I received a letter from a distant cousin, Norman Gentieu, Pierre’s 77-year old grandson, saying that he found me from that review in American Photographer, and guessed that I was related to Pierre Gentieu. Did I know that he was a photographer, and that the Hagley Museum in Delaware has a complete set of his photographs?

I had NO idea!

It was an extraordinary letter from my cousin, and it explained why I was so drawn to photography and was kind of good at it, Could it be genetic?

The Hagley Museum told me that the Historical Society of Delaware had Pierre’s entire set of 354 glass plate negatives. The Historical Society let me borrow them to make prints, 10 glass negatives at a time, which was amazing.

I made archival prints from them — not the albumin prints of Pierre’s day, but the equally distinctive, and now-vintage gelatin silver prints of the twentieth century. I made a hand-bound album with the prints. And then I set out to find out more about my photographer ancestor.

Pierre was only 18 years old when he immigrated, alone, to America from Orthez, Lower Pyrenees, France. It was 1860, and he stayed with his aunt and uncle in a room above their Darrigrand French bakery in Brooklyn. When it got cold, Pierre moved to New Orleans, where it was warmer and they spoke French. He joined the Orleans Artillery state militia, then the Civil War broke out, and the militia was absorbed into the Confederacy. Pierre was the first in his company to step out of line.

He joined the 13th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry because he liked their uniforms. They were dubbed the “Dandy Regiment.” He fought in nine Civil War battles, and after the war, married Sarah Albina Weed, the sister of his tent mate and friend who taught him English. Pierre and Binie had six children — four boys and two girls.

Pierre came from a family of breveted chocolatiers. The family legend was that they made chocolate for the king! So after the Civil War, Pierre and Binie settled down in New York, where Pierre opened two French bakeries and then a restaurant. But he ran into terrible debt, so he had to sell the restaurant.

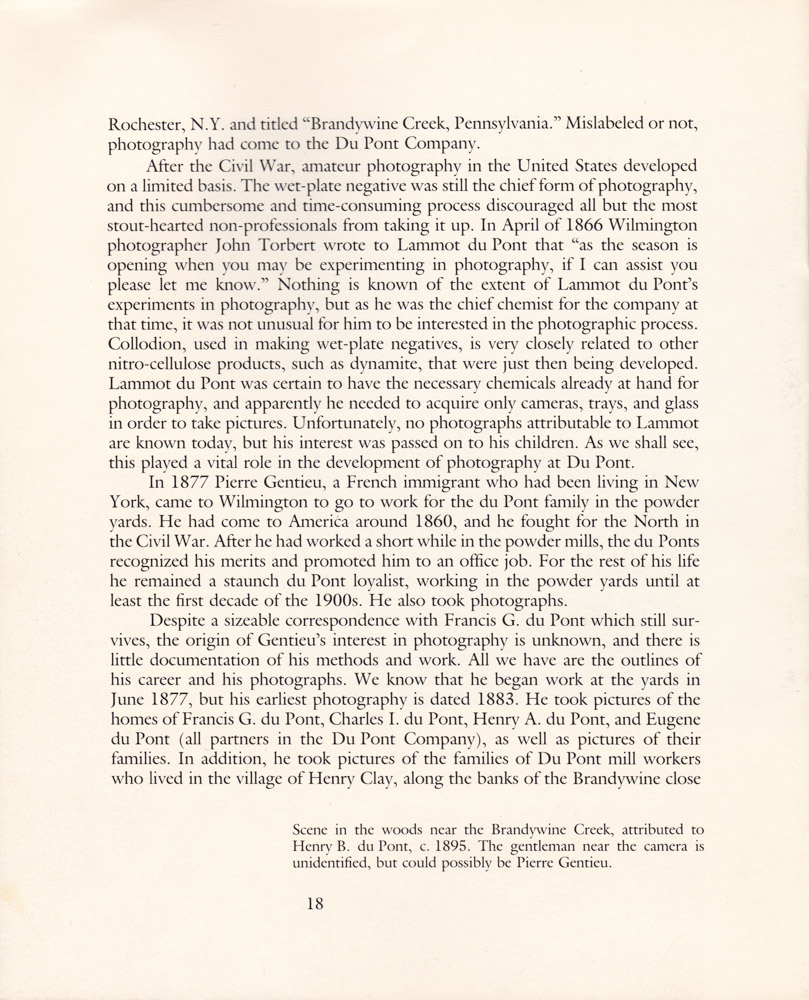

It was 1877 and Pierre was 35, with a five-year old boy, a crawling baby, and a pregnant wife. Pierre was in deep trouble! But alas, he found employment at the DuPont Powder Company in Delaware. The company, being French, making gunpowder, and wanting to help out Civil War veterans, gave Pierre his second chance.

O

He started as a powder worker, a very dangerous job. But the du Ponts soon recognized his talent when they saw a goauche painting he made of the Lower Yard, and he was promoted to work in the office. You could say that art saved Pierre’s life from the many explosions that were occurring in the powder yards.

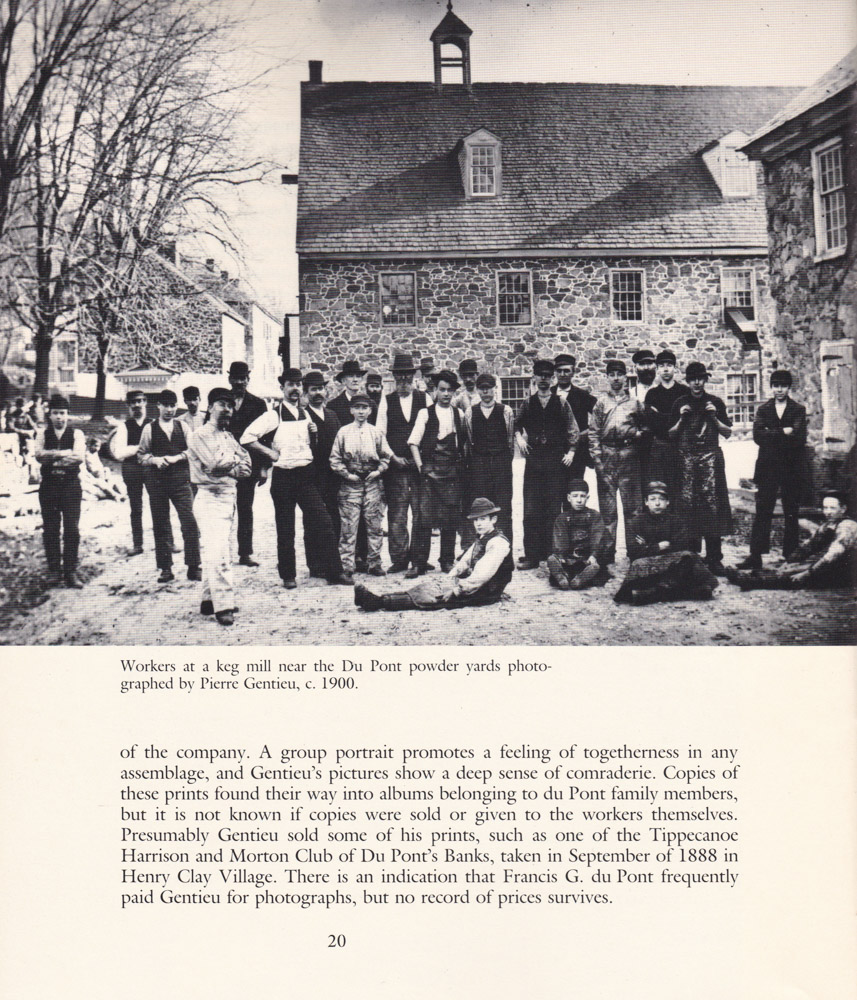

Pierre sometimes brought his camera to work with him, and for a long time was the only person allowed in the yards with a camera.

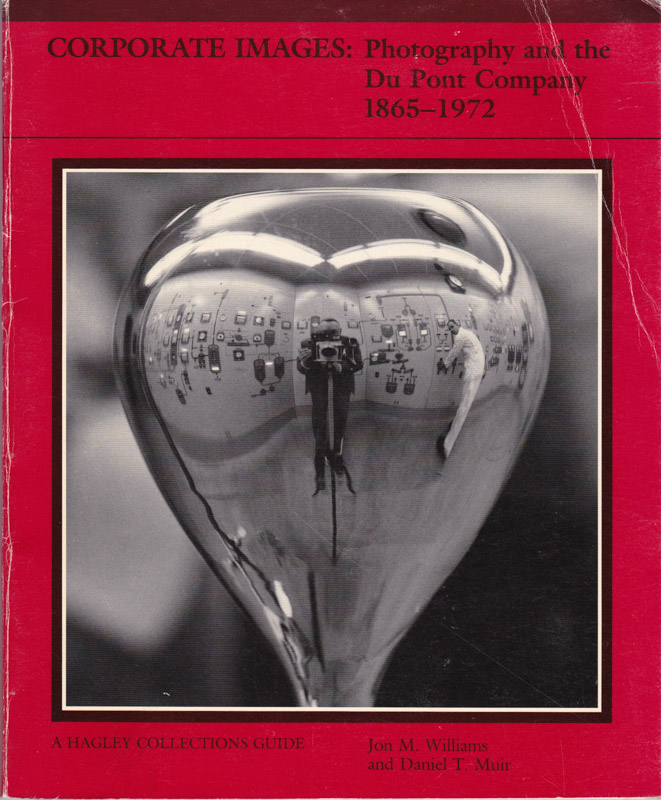

To quote from a clipping from the book, Corporate Images: Photography and the Du Pont Company 1865 – 1972, which the Hagley Museum and Library sent me in 1992 as an introduction to Pierre’s photography:

“Gentieu’s photography was very straight forward, with simple camera angles and poses dictated not only by his equipment, but also by his clear minded approach. He was a gifted amateur photographer who desired to show things distinctly in his pictures. For this he was encouraged by the officers of the DuPont Company, and we can be thankful that he has left us the benefit of his vision. His photography was to leave a mark in the history of the company he worked for so faithfully for so long.”

To have found this connection to my roots has been so profound. If it hadn’t been for a photo credit, if it hadn’t been for Norman looking me up, if it hadn’t been for the Hagley keeping Pierre’s collection with his name on it, I never would have known.